A Look at Olympic Boycotts

|

As the 2022 Winter Olympic Games in Beijing approach, scrutiny on China as a host is back in focus. Its on-going record of human rights abuses - most recently, between the treatment of its Muslim minority to the subjugation of Hong Kong - is depressing. And, it's a legitimate question on whether such a regime should be showcased as host of a "sportswashing" event like the Olympics.

That this conversation is happening shouldn't come as a surprise. It was certainly previewed in the contest to host these Games. As more palatable candidates dropped out of the bidding race, the International Olympic Committee (IOC) was left with two options in 2015: Beijing and Almaty. Despite experiencing similar concerns ahead of its hosting of the 2008 Summer Games, China really was seen as the lesser of two evils...Kazakhstan was and is no humanitarian state, either.

So, Beijing it is, unless the IOC inconceivably decides to move the event. So, the calls for an Olympic boycott have happened. Some of it is political grandstanding - in the United States, at least, an easy way to pressure the current administration while preaching righteousness. But athletes are chattering, too, while China remains defiant. For now, the U.S. Olympic Committee has reiterated its stance against a boycott.

Which begs the question...do Olympic boycotts even work? Let's look at history. 1956 Melbourne Multiple nations stayed away from Australia's first Summer Games, for a variety of reasons. In response to the Soviet Union's invasion of Hungary just before the start of the Games, Spain, Switzerland, and the Netherlands pulled out. Egypt, Lebanon, and Iraq boycotted as a result of the Suez Crisis with Israel. And, China (the Peoples Republic) officially boycotted since China (Taiwan) was allowed entry. At that time, probably only the Netherlands' absence affected general competition quality. And, decades later, it's viewed by the Dutch as "the black page in the Olympic history for the Netherlands". It's hard to argue that the boycott influenced outside events, as the trajectories of the Cold War, Middle East crisis, and Chinese territorial fights continued well past 1956. 1964 Tokyo Due to political discrimination at the separate Games of New Emerging Forces (GANEFO) in 1963, those participating athletes were barred from the 1964 Games. Thus, Indonesia and North Korea pulled all their athletes from the Olympics. The resulting legacy of the 1964 boycott is simply a missed opportunity to see North Korean Sin Kim-Dan, then the world record-holder, compete in the women's track 800 meters. That had promised to be one of the more intriguing events on the track. As for GANEFO? Built as a direct competition to the Olympics by Indonesia, it was officially dead by 1970.

1976 Montreal

In 1976, New Zealand's rugby team toured South Africa despite an international sporting embargo on the apartheid-led nation. In response to New Zealand not being expelled from the 1976 Games later in the year - and despite rugby not being an Olympic sport - more than 20 African nations led a boycott. By far the most prolific multinational political effort at the Games, the success of the effort is nuanced. Some argue that the massive boycott did help repeal apartheid in the longer end, as it shined a wider light on South Africa's racist policies (and Black African unity against it), as well as spearheading immediate resistance to rugby's friendliness with South Africa within New Zealand itself. On the other hand, by far the lasting commentary of a Montreal 1976 retrospective is the massive debt incurred in staging the Games, not the boycott. And, track fans (again) were deprived of potentially stirring matchups, particularly from East African runners. Note, Taiwan also boycotted these Games, as a result of not being able to use the moniker Republic of China, in IOC deference to the People's Republic of China (who again didn't even enter). 1980 Moscow In by far the biggest Olympic boycott effort, the United States led more than 60 other nations, including Canada, Japan, and West Germany, to skip the Games in order to voice opposition to the recent Soviet invasion of Afghanistan, and to not use Games participation as "implicit approval" of Soviet aggression. With many leading nations absent, and many individual athletes from participating nations similarly staying home, competition was hit hard and the host nation was seemingly chagrined. But not chagrined enough to change its Afghanistan policy: the Soviet Union remained in the country until 1989. In the U.S., the boycott is very much seen as ineffectual, and devastating for the more than 400 American athletes prevented from competition. Even the U.S. Olympic Committee weighed in last year against boycotts after continued remembrance of 1980.

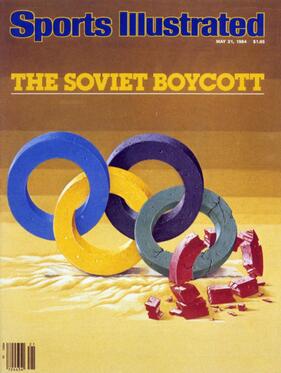

1984 Los Angeles

Announcing a distrust of security for its athletes, the Soviet Union led a boycott of the Los Angeles-hosted Games in 1984. rather acknowledged as a tit-for-tat move for 1980, it is also widely seen as having failed. While 13 other Soviet-tied nations also stayed home, the Games most certainly persevered. Buoyed by excited media coverage, Los Angeles 1984 is as well-known for who did compete as much as who didn't. Romania and Yugoslavia bucked the Soviet block and thrived. P.R. China appeared for the first time since 1952. The Games were also a financial hit, providing a funding model that is today's top sports sponsorship property. The Soviets and friends didn't come? The hit to competition didn't seem to matter to the massive audiences in the end, as Los Angeles brought the party back to life. 1988 Seoul Despite not having official diplomatic relationships with the communist bloc at the time, South Korea managed to avoid a significant boycott effort. North Korea, after being denied an unlikely request to co-host in a significant manner, stayed home, along with their ally Cuba. Otherwise, Seoul 1988 set a record for participating nations (159) and, with all sporting world powers (sans Cuban baseball players and boxers) present, full competitive action was restored One take on whether this boycott was a success is looking at when South Korea again hosted a Games with Pyeongchang 2018. Then, in order to ensure North Korean participation, a series of "unity" measures were integrated. Some might argue that a line might be drawn back to the lessons of 1988's failed negotiations, but the Olympic concessions proved only a temporary respite, as any goodwill generated in 2018 is certainly forgotten now. Plan on another round of North Korean angst if and when South Korea hosts again.

So, where will today's boycott talk go? There are a lot of beginning similarities to the U.S. approach with Moscow 1980. A call to move the Games, then to boycott by determined politicians. A president increasingly scrutinized for how hard-line he is with a geopolitical enemy. A legitimate humanitarian transgression by the host, deserving of significant and perhaps symbolic international reaction.

Too often, though, those championing a boycott overlook those directly affected, the athletes. And athletes remain the heart of the Games; despite any fanfare and ceremony, it's about the ultimate camaraderie of competition. If 1980 is a guide, one should expect the significant public relations risk of a litany of athlete disappointment stories. And, times have changed. The Games are bigger, and athletes and sport federations have much more at stake commercially. Although there are a myriad of world championships, world cups, and grand prix events in any given sport, the Olympics remain the ultimate opportunity for an athlete to showcase their hard work and career. What to do? Though some individuals may be at peace with making a personal choice to not compete, it would be a tough call today to to ask an entire delegation to step down. Athletes deserve to be the priority, and not victims of political retributions. Perhaps the focus should be to pressure the IOC to not award the Games to questionable spots in the first place. That certainly may be one purpose behind the IOC's targeting a single "preferred" future host for the next few summer editions. While Beijing 2022 will probably proceed as planned, at least there's a blueprint to better avoid a problem in the future.

A version of this opinion originally appeared on gamesandrings.com.

|

.thumb.jpg.e94c7df9233a633da4e2f7f744a292c6.jpg)

Recommended Comments

Create an account or sign in to comment

You need to be a member in order to leave a comment

Create an account

Sign up for a new account in our community. It's easy!

Register a new accountSign in

Already have an account? Sign in here.

Sign In Now